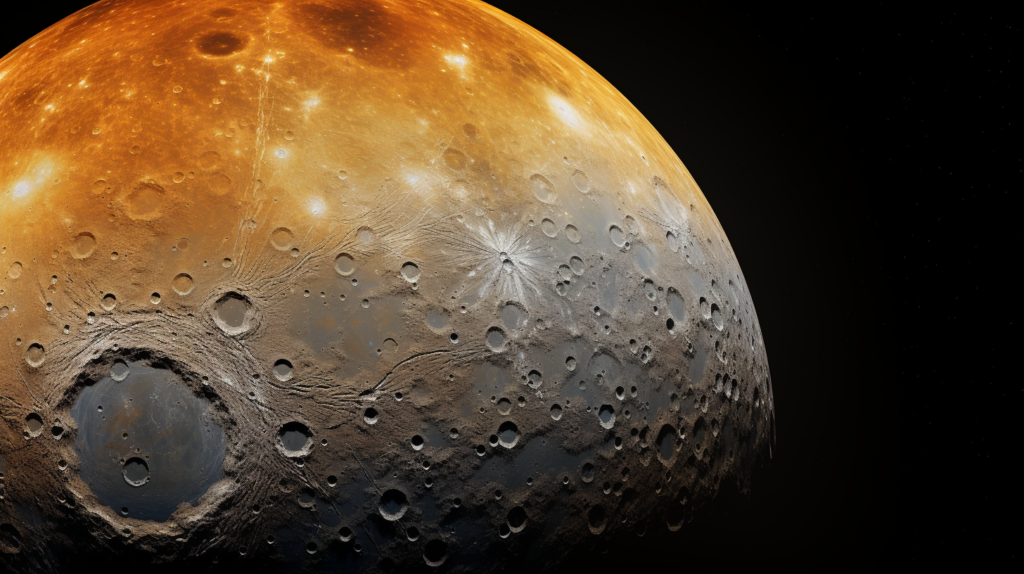

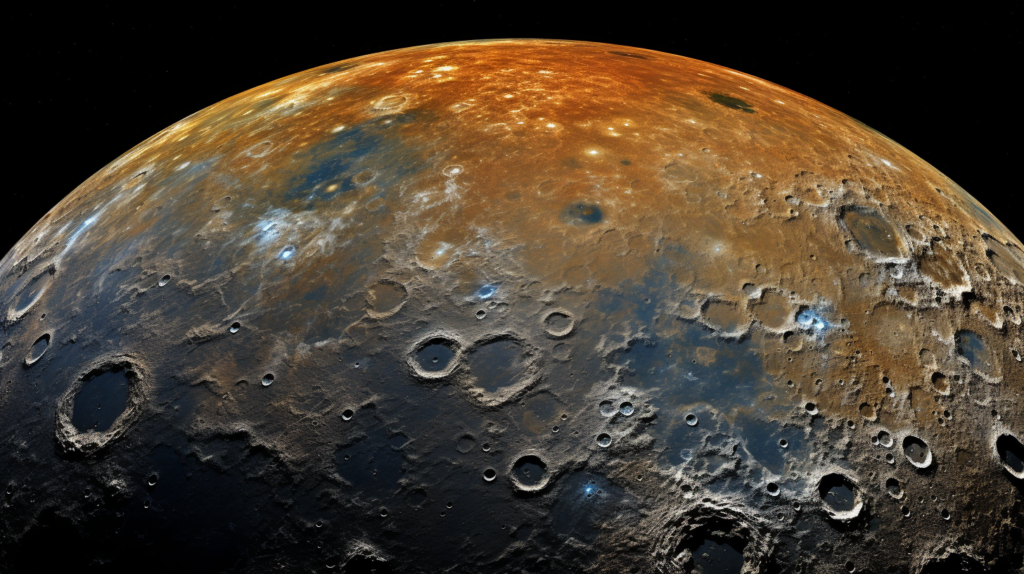

The smallest planet in our solar system, Mercury is often overlooked in favor of its larger, more dramatic planetary neighbors. But Mercury harbors many fascinating secrets beneath its airless, cratered exterior.

From its scorching hot days to its frozen water ice deposits, Mercury continues to surprise scientists over 75 years after its exploration began. Read on to discover 20 asatounding facts about Mercury – the first rock from the Sun. You’ll never look at this little planet the same way again!

- Mercury’s Slow Rotation and Long Days

- Mercury Has a Huge Iron Core

- Mercury’s Extreme Temperatures

- Bizarre Terrains and Battered Surface

- Mercury Has Almost No Atmosphere

- Mercury’s Magnetic Field

- Water Ice Exists on Mercury

- Mercury Was Named After the Roman God Mercury

- Mercury Has Been Known to Ancients for Millennia

- We’ve Only Explored Mercury Superficially

- Mercury Has Unclear Origins

- Mercury Has a Unique Orbit

- Mercury Boasts the Greatest Orbital Eccentricity

- Mercury Backed Up Galileo’s Heliocentric Theory

- We Once Thought Mercury Was Tidally Locked

- Mercury Has Strange Radar-Reflective Deposits

- We Can See Mercury Transits from Earth

- Mercury Exhibits Gradual Shifts in its Orbit

- Even More Facts About Mercury

Mercury’s Slow Rotation and Long Days

Mercury rotates incredibly slowly on its axis – with one Mercurian day equivalent to 58.7 Earth days! This means the tiny world has one of the longest days in the solar system.

But Mercury orbits the Sun very quickly, with 1 Mercurian year lasting only 88 Earth days. So even though a solar day on Mercury lasts 176 Earth days, a Mercurian only has to wait 88 days between two noons. This extreme disparity between rotational and revolutionary periods gives rise to very unusual diurnal conditions on the planet.

Mercury Has a Huge Iron Core

Mercury has an abnormally large core relative to its size. In fact, with a radius of about 1,100 to 1,200 km, Mercury’s core makes up a whopping 85% of the planet’s radius!

Scientists believe Mercury’s oversized core is composed primarily of iron and accounts for an even larger fraction of the planet’s total mass – perhaps as much as 70%. This suggests that Mercury’s outer shell is relatively thin and dominated by silicates.

Mercury’s Extreme Temperatures

Lacking an atmosphere to regulate temperature extremes, Mercury endures incredibly hot days and freezing cold nights. Surface temperatures on the planet’s sun-scorched day side can reach 800°F (430°C). But on the dark night side, temps plummet to -290°F (-180°C).

That means the tiny world experiences temperature variations of over 1,100°F (600°C) as it completes each revolution around the Sun! These dramatic swings arise because Mercury has virtually no atmosphere to trap heat on the night side or transport it around from the hot dayside.

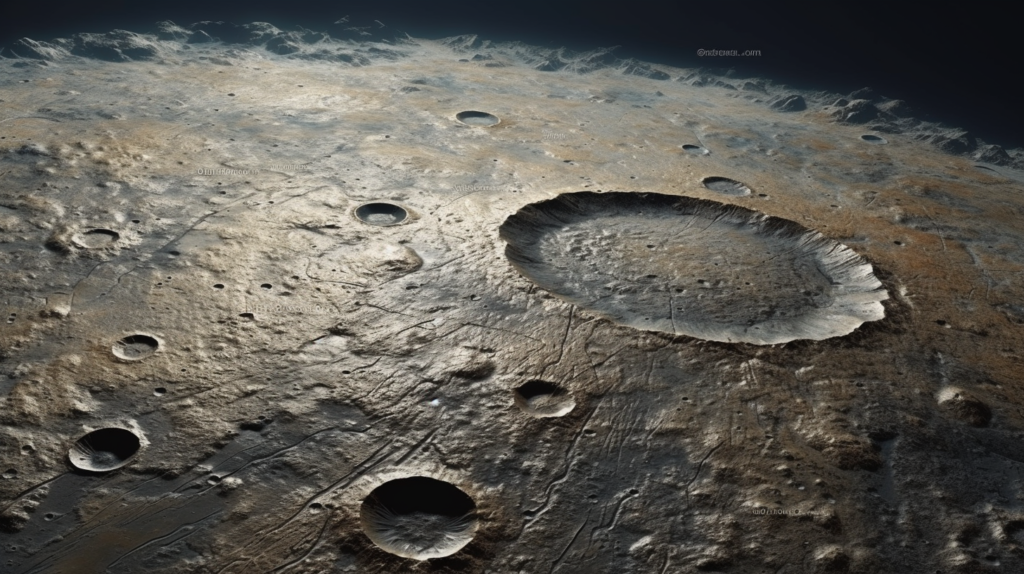

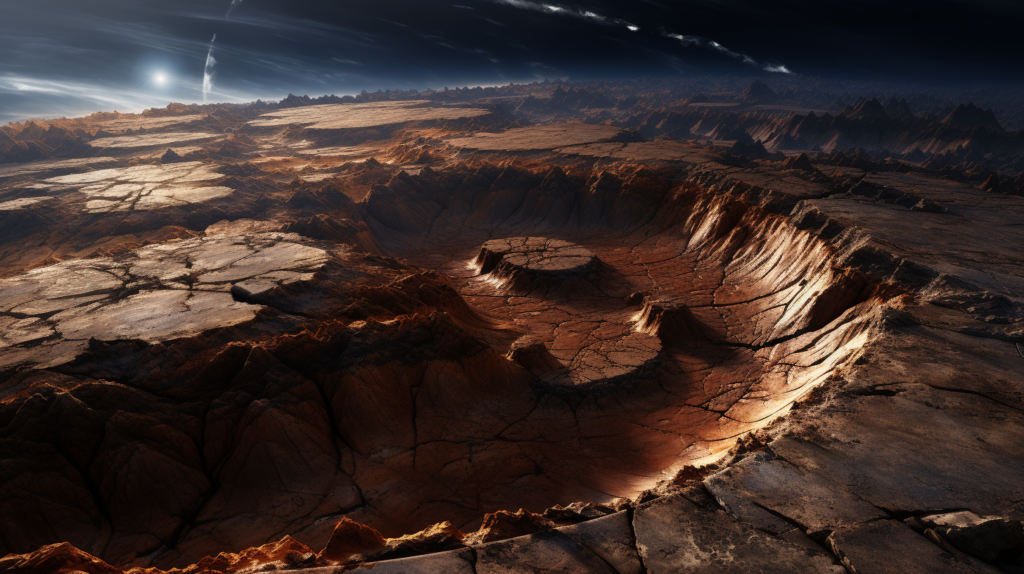

Bizarre Terrains and Battered Surface

Mercury’s ancient, heavily cratered landscape tells the story of a surface that’s endured billions of years of meteoroid bombardment. The planet also sports some unique – and geologically young – terrain types, like smooth plains formed by ancient lava flows:

“A prominent and geologically recent feature of Mercury’s surface is the presence of smooth plains. These plains are expansive, relatively crater‐free regions that dominate the high northern latitudes and occupy intercrater areas across much of the rest of the planet.”

As well as strange landscapes possibly produced by planetary contraction:

“As Mercury’s interior cooled over geological time, the whole planet contracted, causing global-scale thrust faults that ran for hundreds of kilometers and lifted sections of crust up to several kilometers high. This formed “lobate scarps” that wend across Mercury’s face for up to a thousand kilometers.”

So while Mercury’s surface bears the hallmarks of battering over billions of years, unusual landforms point to more recent geological activity as well.

Mercury Has Almost No Atmosphere

With an atmospheric pressure just 1 trillionth that of Earth’s, Mercury might as well be considered airless. Any vestigial atmosphere captured from the solar wind is so thin that it can only sustain itself on the planet’s dayside, where solar heating temporarily offsets loss of atmospheric molecules into space.

This lack of a substantial atmosphere allows meteoroids to continually pelt Mercury’s surface. Over time, this nonstop bombardment has led to the extensive cratering observed across the planet.

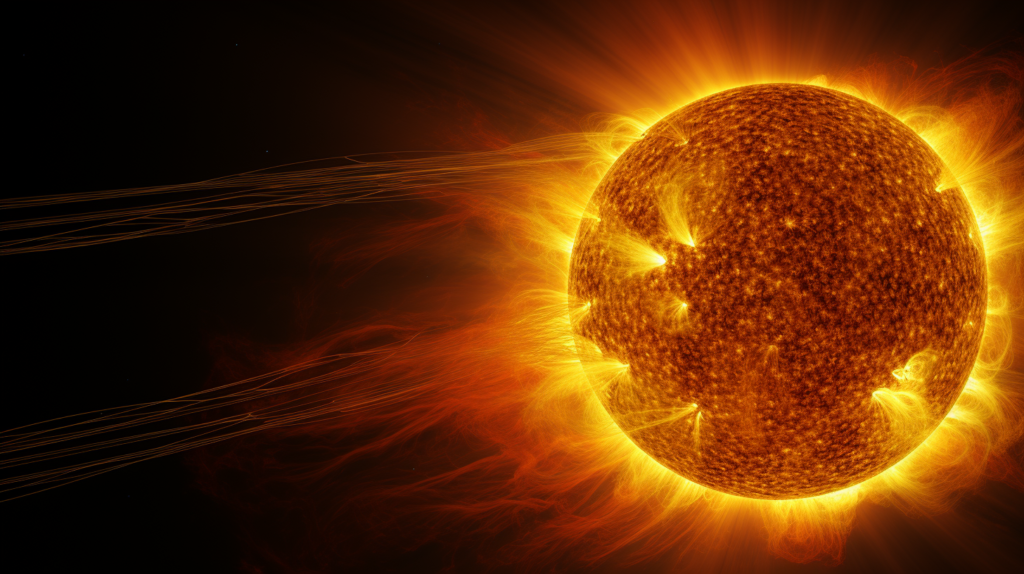

Mercury’s Magnetic Field

Despite its small size, Mercury manages to hold onto a global magnetic field – a surprising fact given how close it orbits the Sun. While just 1% the strength of Earth’s magnetic field, scientists think Mercury’s magnetosphere is driven by motion of molten iron alloys in the planet’s sizable core:

“Mercury’s global magnetic field is dominantly dipolar, aligned with the spin axis, and centered at the planet’s center of mass. […] Convection driven by secular cooling in an electrically conducting molten outer core generates Mercury’s magnetic field.”

This miniature magnetosphere shields part of the planet’s surface from bombardment by the solar wind – though given Mercury’s weak field, the Sun’s particles still get through in some areas.

Water Ice Exists on Mercury

Despite searing daytime temperatures, deposits of water ice likely exist in permanently shadowed crater regions near Mercury’s poles. Evidence from Earth-based radar imaging and MESSENGER orbital data bolster the idea that water ice brought by comet impacts has accumulated in these cold traps over geological time. As described in observations of Mercury’s polar regions:

“Areas of permanent shadow host water ice, which was discovered in observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft. The ice is most likely delivered by impacts from comets and is stable inside cold polar craters, where summer temperatures never exceed about −200°C.”

So while Mercury’s surface is extremely inhospitable to life as we know it, water ice trapped in shadowed craters raises intriguing questions about the planet’s habitability.

Mercury Was Named After the Roman God Mercury

The planet gets its English name from the Roman god Mercury – the swift messenger of the gods. This was an apt choice, as Mercury zips around the Sun faster than any other planet.

The ancient Greeks called the world Ερμής (Hermēs). Their version of the god Hermes fulfilled a similar role as messenger and conductor of souls into the afterlife. Plus, the god Hermes was said to be clever, crafty, and quick – all fitting descriptors for the fleet-footed innermost planet.

Mercury Has Been Known to Ancients for Millennia

As the innermost planet and one that exhibits notable motions against background stars, Mercury has been observed for thousands of years. The first known recorded sightings of the planet date all the way back to the Sumerians around 3,000 BCE!

Ancient Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, and Chinese astronomers were also all familiar with Mercury’s movements. For example, 4th century BCE Greek philosopher Plato even made mention of the planet in his dialogue Timaeus.

And by 265 BCE, Greek astronomers were already aware that Mercury orbits the Sun:

“By at least the 4th century BCE, Greek astronomers were aware that Mercury orbited the Sun.”

So while detailed study awaited the invention of the telescope, Mercury’s dramatic motions did not escape early sky-watchers – allowing it to become one of just five planets recognizable to the naked eye.

We’ve Only Explored Mercury Superficially

To date, only two spacecraft have visited Mercury and gathered close-up observations:

- Mariner 10 (1974-1975) – 3 quick flybys

- MESSENGER (2008-2015) – 4 flybys + 4 years in orbit

These missions have offered tantalizing glimpses of Mercury’s secrets, imaging about 45% of the surface at resolutions down to 250 meters per pixel. But much more remains undiscovered on this little world, awaiting future orbital and landing missions to reveal its hidden face.

As noted on our past missions to Mercury page:

“Much remains to be learned from orbit about Mercury’s composition, structure, magnetosphere, polar deposits, and much more. A landed mission could directly sample surface materials in a range of terrains.”

So while the MESSENGER orbiter collected reams of valuable data, additional missions this century and beyond promise to peel back further layers around Mercury’s origins and geological evolution.

Mercury Has Unclear Origins

Despite being the smallest and innermost planet, the precise details of Mercury’s formation and early history remain unclear. Leading theories posit the world formed from the same primordial materials as other terrestrial worlds. But its high metal content and oversized core defy easy explanation.

Proposed ideas as described on our page on Mercury’s origins include:

- Formation in a localized region of the solar nebula with high metallic abundances

- Stripping of an original silicate mantle via giant impact(s)

- Photodesorption of silicates after formation

However, significant mysteries around the planet’s origins persist. Further orbital data and eventual surface samples will help narrow down how this strange little planet came to be.

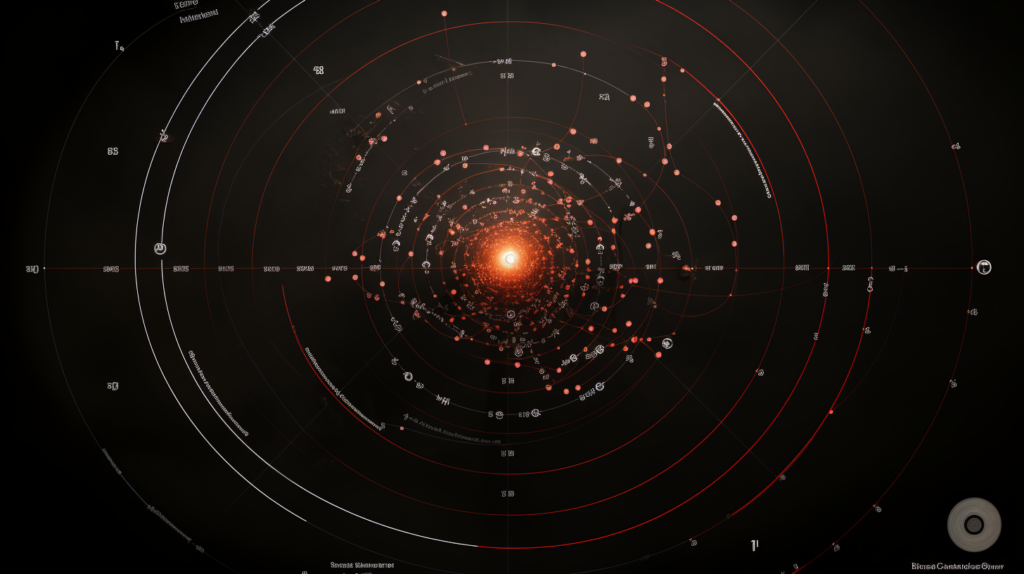

Mercury Has a Unique Orbit

Mercury follows an egg-shaped, highly eccentric orbit around the Sun. At perihelion (closest approach), Mercury gets as near as 29 million miles (47 million km) to the Sun. But at aphelion (most distant point), it recedes out to 43 million miles (70 million km) – a difference of over 14 million miles!

No other planet experiences such a variation between closest and furthest solar distances. This extreme orbital eccentricity arises from a spin-orbit resonance where Mercury completes exactly 3 rotations around its axis for every 2 revolutions around the Sun.

Over time, gravitational perturbations from other planets enhance eccentricity growth driven by this 3:2 resonance. The result is Mercury’s uniquely lopsided orbit, taking it from roasting hot infrequent perihelion to relative cool of aphelion and back every 88 days.

Mercury Boasts the Greatest Orbital Eccentricity

Zooming around the Sun in just 88 days, Mercury traces the most eccentric orbit of any Solar System planet. Its orbital eccentricity of 0.206 far exceeds that of Mars (0.0934) and dwarf planet Pluto (0.248). This means Mercury experiences the greatest difference between closest and furthest approach to the Sun.

What drives this extra eccentricity? A spin-orbit resonance wherein Mercury completes exactly 3 spins around its axis for every 2 orbits of the Sun. Also known as a 3:2 resonance, this gravitational coupling amplifies eccentricity growth over billions of years – pushing Mercury’s orbit to extremes no other planet attains.

Mercury Backed Up Galileo’s Heliocentric Theory

In the early 17th century, Galileo Galilei’s observations of Mercury’s orbital motions provided evidence in favor of the Sun-centered (heliocentric) model of the Solar System. Mercury exhibits an orbital effect known as retrograde motion, appearing to periodically reverse direction against the stellar background.

The leading geocentric model failed to account for these observed retrograde movements. But Galileo showed how Mercury’s motions make sense when viewed relative to a Sun-centered system – lending key support for what became the Copernican model of the Solar System.

So while the Italian astronomer didn’t discover Mercury itself, careful observations of the swift little planet helped cement the most profound rearrangement in our cosmic worldview to date!

We Once Thought Mercury Was Tidally Locked

For decades up through the mid-20th century, astronomers believed Mercury’s rotation was tidally locked to match its 88-day orbital period. This presumed synchronous rotation would result in permanent dayside and nightside hemispheres.

But radar observations in 1965 demonstrated conclusively that Mercury completes exactly 3 rotations every 2 orbits – not 1:1 as previously thought. This finding dashed the assumption of synchronous rotation, instead revealing that Mercury experiences eternal sunrises over craters and scarps never before seen.

So ending a long-held tidal locking theory, radar glimpses of Mercury unveiled a world experiencing some of the most extreme temperature swings this side of solar orbit!

Mercury Has Strange Radar-Reflective Deposits

In the 1990s, radar astronomers identified strangely reflective features near Mercury’s north pole. These radar-bright deposits occupy unusually non-reflective lowlands confined to high northern latitudes. Researchers suggest the deposits could consist of water ice, sulfur compounds, or even an iron-nickel alloy from Mercury’s core!

While small, these reflective North Pole features hint at complex geological processes possibly involving volcanism and tectonics:

“The enhancement in radar reflectivity and high radar polarization ratios imply these polar deposits have different compositions and textures than the surrounding regions. Leading possibilities include some form of ice or sulfur-bearing compounds.”

So very recent geological activity combined with possible cometary water deliveries give rise to unique radar-bright terrain – revealing Mercury as a world still capable of surprise right up to the present day.

We Can See Mercury Transits from Earth

Roughly 13 times per century, Mercury passes directly between Earth and the Sun in an event known as a transit. During these rare alignments, skywatchers can glimpse tiny Mercury as a faint dot traversing the Sun’s bright disk.

Mercury’s tiny size means transits last only several hours and require proper eye protection for safe viewing. But observing or photographing Mercury’s silhouette against our star provides a unique opportunity to perceive an inner world that otherwise remains lost in the Sun’s glare.

The most recent Mercury transit took place on November 11, 2019. But the next chances don’t come until 2032 and 2039 – so mark your calendars to catch fleeting Mercury during these singular events!

Mercury Exhibits Gradual Shifts in its Orbit

Like all planets, Mercury experiences slight perturbations in its orbit over time. Radar observations show its average orbital distance around the Sun changes by about 0.1% every million years – the equivalent of 575 miles (925 km)! Such long-term “precession” arises from gravitational tugs among Solar System worlds.

Even More Facts About Mercury

As we’ve seen across these 20 facts, Mercury is a world of extremes and intrigue. Despite being the smallest and innermost planet, it hosts incredible geological features, a surprisingly strong magnetic field, and deposits of water ice in permanently-shadowed regions.

Mercury’s irregular rotation, huge iron core, and highly eccentric orbit give rise to wild temperature swings, strange terrain types, and the greatest orbital variation of any Solar System world. Upcoming missions promise more revelations about mysterious Mercury – but for now, we’ve only scratched the surface of this tiny dynamo planet nearest the Sun.